In applied statistics you often have to combine data from different samples or distributions. One of the most frequently used operation here is to add means and expected values. For instance, you could sample people’s leg length, body and head height. The result when adding these means? It is the average body height, I hope!

Relationship between expected value and mean

My reasoning, why adding means works, will be based on expected values. The expected value of a random variable is defined as

where is the probability of receiving a specified value

when drawing from a specified population. In case you already received a sample from an unknown population, you may think of the probability for each value, which

can take, to be 1/n. You then receive the well-known formula

Mean or expected value; the subsequent explanation is valid either way.

Adding two random variables

Now let’s assume we wanted to add two random variables – say and

– and calculate the expected value. Instead of

we now need to give the probability when the random variable

takes a value

AND the random variable

takes a value

. We are going to call this probability

With two variables we now have to process all possible combinations of and

. Here is the result:

We can split the right-hand side into two separat sums. As it doesn’t matter whether you sum the values for or the ones for

first, we can swap the order of the second term.

This is where it gets tricky. On the one hand, we can drag out of the sum of all

, because

is constant in terms of

. The same accounts for

.

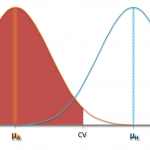

Further we can simplify the probabilities. See, adding for all

will result in

and vice versa.

But what do we have here? Each of the right-hand side’s terms is equal to the definition of an expected value!

Some comments

The last equation has shown that we can, indeed, add expected values. Have you noticed that we didn’t make any assumptions regarding the independence of the random variables? Hence, the rule holds even if your random variables are correlated! And remember the introductory example? We used a continous measure there. Just replace all sum signs by integral signs and you’ll see that the rule works with continous random variables too.

Always keep in mind that you can apply the addition to means as well. So, the mean can be calculated by adding

and

. But this is what most people intuitively do already.

(4 votes, average: 4.75 out of 5)

(4 votes, average: 4.75 out of 5)

Leave a Reply